- Home

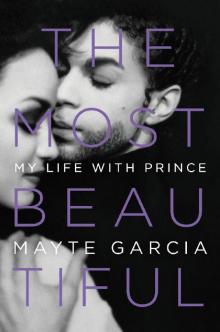

- Mayte Garcia

The Most Beautiful Page 2

The Most Beautiful Read online

Page 2

if u ever get the chance 2 travel back 2 ancient dance

I feel that same certainty about my husband, my soul’s mate. I believe—and so did he—that he was my lover in one lifetime, my brother in another; maybe we were sisters, mother and child, or even mortal enemies. At the moment of each birth, we were poised, a breath apart, destined to come together in some capacity and fated to part, knowing we would inevitably come together again. We might not immediately know each other’s name each time we met, or recognize the face, but we each knew that names and faces were the least relevant aspects of the other. I recognized my beloved, though not right away, and he treasured me, though he didn’t know how to keep me.

Prince Rogers Nelson was born June 7, 1958, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His mother, Mattie, was a jazz singer. His father, John, was a musician who went by the stage name Prince Rogers. Prince spoke very little about his early childhood. He did tell me he remembered being locked in a closet sometimes. John and Mattie split up when Prince was ten, and he was like a kite without a string, sometimes living with his mom and stepfather, sometimes with his dad, sometimes crashing with friends. Prince was a skinny little kid, who topped out at five feet two, but he was still an excellent basketball player at Bryant Junior High, where he became friends with Andre Simon Anderson, who later went by André Cymone when he toured with Prince. Two things Prince would take with him from an adolescence that was as difficult as you might imagine adolescence could be for a short, skinny, black dude were his love of basketball and his friendship with André.

On November 12, 1973, while they were somewhere shooting hoops, I was born on a military base in Enterprise, Alabama, where my dad was in army flight school. My mother, Nelly, and my father, also named John, are both Puerto Rican born and raised. She was—and is—a stunner: a voluptuous, headstrong beauty. Her strict Catholic parents tried hard to keep a lid on her, but my mother was—and is, for better or worse—a bold free spirit who never did well in the role of caged nightingale. Really, it’s the laws of physics; her strict upbringing made her want to rebel and get off the island. She wanted to leave Puerto Rico, so she only dated men in the ROTC, hoping for a ticket out.

Dad was a great date, handsome and kind, a former body-builder who’d won the title of Mr. University of Puerto Rico. He’d followed his father into the military and rose through the ranks to become an officer, something his own father never did. After they’d been dating for a while, Mama realized she was pregnant. And not just a little. She was six months along. Both families swooped in and basically forced them to get married immediately.

Mama still mourns the fact that she never got to have a proper wedding, which made her all the more thrilled to see me marry Prince with all the trimmings. My dour Catholic grandmother (whose own father was black), wasn’t at my wedding, but she told me on the phone, “Well, at least he’s light-skinned. And he is who he is. So I’m okay with it.” And that tells you everything you need to know about my grandmother.

My big sister, Janice, was born in 1969, and my parents commenced a typical military family life, moving from base to base, which my mother quickly realized was not the post–Puerto Rico life she had hoped for. When Jan was four, they decided to have another baby, desperately hoping for a boy. Dad was slated for an important test flight the day I was born. He would have been first in his class, but missed the test and came in second. Janice was thrilled to have a little sister, but when my mother heard “It’s a girl!” she was so mad she refused to see me.

They whisked me away, and by the time they finally brought me in to see her, I had casts on both legs. I’d been born with severely inverted legs. An orthopedic specialist, who just happened to be there that day by a stroke of luck—or perhaps by fate—explained to my parents that my crooked little limbs would have to be straightened, first with the casts and then with painful braces that I’d have to be kept in for three years, forcing the bones and joints to develop in a normal position.

My mother was fierce about those casts, as she is about pretty much everything when it comes to the people she loves. She was adamant that my legs were going to be normal and strong. The standard three-year treatment was accomplished in eighteen months because she kept the braces—little boots connected by a metal bar—firmly on me 24/7. Family members would shake their heads, take pity on me and try to remove them, but Mama prevailed and the boots stayed on. I have scars from an infection that developed when the braces became too tight, but I can’t complain about these legs of mine. They’ve served me well. This is probably the beginning of my ballerina’s dance-through-the-agony disposition. Before I learned to walk, I learned that sometimes life requires a girl to be a tough little cookie.

My mother adored the name Mayte, a Spanish conjunction of Maria and Teresa, the Basque word for “beloved.” As a teenager, she’d seen this name in a novella, torn out the page, and kept it posted on her bedroom wall for years. Janice’s middle name is Mayte, but the conventional world of the late 1960s decreed that children were better off with “American” (meaning “white”) first names, and that temporarily swayed Mama. When I came along four and a half years later, she figured if she couldn’t have the boy she hoped for, she was by God going to name this girl exactly what she wanted to: Mayte Jannell, my middle name being a combination of John and Nelly.

When Prince and I were first hanging out—not yet lovers, just friends and collaborators—he got it in his head that I should change my name to Arabia.

“Man, it’d be cool if your name was Arabia,” he kept saying.

Prince had a way of getting people to go along with ideas like that. They’d get swept up in his genius, not just for music but also for creating characters. He’d see some unique aspect of a person, and he’d highlight that. He never bullied anyone into anything, just nicely suggested that it would be really cool if a person changed her name to… oh, I don’t know—Apollonia, maybe. Or Vanity. How cool would that be?

The fourth or fifth time he said to me, “Wouldn’t it be cool if you changed your name to Arabia?” I flatly said, “No. That would not be cool. My mom would kill me.”

In my mind at the time, the wrath of Mama loomed larger than the favor of a thousand rock stars.

Mama was raised in a strict Catholic home. She dreamed of becoming a dancer, but that was not an option. She tried to enroll my sister in dance lessons, but Jan was a rough-and-tumble tomboy who would have nothing to do with our mother’s ambition to either be a ballerina or raise one. Jan was the sporty one, playing volleyball and soccer; I was the girly girl, living in tutus and “turn-around dresses.” (Gia is turning out to be comfortably in the middle, completely herself in a cute little dress with sneakers.) By the time I was three, to Mama’s delight, I was begging to dance, but you had to be five years old to take lessons at most studios. By this time, we’d moved to North Carolina, so it wasn’t hard for my mom to locate a place near the base where no one knew us.

“When they ask you how old you are,” she told me, “do this.” She held up her hand, palm flat, showing five fingers, and I did exactly as I was told after she dropped me off. Whether the ballet teacher believed me or not, she must have figured I was ready, because she took me to the barre and I never looked back. Over the years, no matter how chaotic my home life was, dance was my sanctuary. It wasn’t a task for me to concentrate. I never had to discipline myself to endure the practice. I loved every hour, even when it hurt. I loved feeling the music in my strong, straight bones.

Belly dancing was a big thing at our local YMCA in the mid-1970s, as big as Zumba is now, the thing to do. Mama started out taking lessons for fun but fell in love with it and joined a troupe that did performances and seminars. I’d watch Mama practice back then the same way Gia watches me now, utterly captivated by the rhythm of the tablas and drums, eyes big with the imagined story told by the dance, hands instinctively tracing the movements in the air. Eventually I couldn’t resist; I had to get up and move behind her, the way Gia moves b

ehind me, making a tiny shadow on the wall next to mine.

“Would you like to dance with me at the officers’ wives luncheon?” Mama asked, and she didn’t have to ask twice. I was so on board with that. I had every beat of the music memorized, and I had a natural affinity for the moves. The choreography was ever evolving, which is one thing I love about this art form. To dance like this gives you freedom to express yourself, but it means you have to be in the present—all of which made belly dance the perfect training ground for the work I would later do as a member of the New Power Generation.

All the other ladies were impressed that I could seriously dance. They had to give Mama her props, and she was a stage mom who ate that up. Mama made me a little costume that matched hers—a floaty dream of colorful chiffon, spangled with a galaxy of sequins and dripping with paillettes—but for me, the greatest thing about it was that I got to wear lip gloss. Please understand, people: in my five-year-old mind, lip gloss was the magic elixir that transformed a mortal being into something magical, the most beautiful creature imaginable. My desire for lip gloss was so intense, I’d actually attempted to steal a tube of ChapStick one day at the PX, prompting Mama to call for a security officer, who lectured me into terrified tears. In everyday life, lip gloss was forbidden. Dad had banned it on the premise that it might make me kiss boys. So this was my opportunity. For lip gloss, I would do anything.

Almost anything. Anything but this, as it turned out. Standing backstage, I peeked out at the audience and was overwhelmed by a stomach punch of stage fright that caught poor Mama completely off guard.

“Mayte, that’s our music,” she hissed in a whisper. “We’re on!”

I just shook my head, unable to even form the words, I can’t, I can’t, I can’t.

I stood frozen behind the curtains while she put on a fake smile and went out to wow the officers’ wives on her own. Some kind lady took my hand, led me to a table, and fed me mini doughnuts and milk while Mama did our mother-daughter dance all by herself, glancing my way every once in a while to shoot me the look.

When a Puerto Rican mama shoots you the look, you feel it like a javelin. There was no question in my mind that when she got off that stage, I’d never enjoy another moment of peace, love, or lip gloss for the rest of my life. I sat there stuffing those mini doughnuts into my mouth like they were my last meal. And they were, for a while. My mom didn’t talk to me or feed me for a week. Dad had to take over, and though he fed and cared for me with patience and sympathy, I was crushed—not because she was punishing me, but because I knew I’d humiliated her. I swore to Mama and to myself that if she ever gave me another chance, I would go through with it, and when given another chance, I did.

And I’m glad. The moment I started dancing, the tidal wave of stage fright went out and a tidal wave of euphoria came in, sweeping me through the performance, filling me with an energy I had no name for. I was quickly addicted to the powerful bliss I felt onstage. Mama and I started getting invitations to dance at restaurants and parties. We started getting a little bit famous around town. When I was seven, a syndicated news show called PM Magazine came and did a story about us, which was amazing, but I was starting to get a sense of myself as a dancer—as an artist—and it had nothing to do with being paid or noticed.

After we’d been performing together for a while, I told Mama, “I want to dance by myself. I don’t want people to think I’m just copying you.” The truth is, I wanted people to notice her when she was dancing, and when I was there, a lot of the attention was directed my way. I wanted Mama to have her hard-earned moment in the spotlight.

Dance was my refuge, as life at both school and home became more complicated. Back then, you didn’t see a lot of little Latina girls in a North Carolina elementary school. Kids used to ask me, “Are you white or are you black?”

“Neither,” I’d say. “I’m Puerto Rican.”

They’d wrinkle their noses and ask, “What’s that?”

I tried to tell them about my grandmothers on a beautiful island that is, yes, part of the United States, but no, not a state exactly, and no, it’s not the same as Mexico. The white kids didn’t accept me because I wasn’t white enough, and the black kids didn’t accept me because I had “good hair.” After school, I was always running away from somebody, making a beeline for the bus, doing my best to avoid getting beat up.

Daddy loved taking the family to a nice restaurant for dinner every once in a while, and when he stepped up to the hostess podium, he always gave the name Rockefeller. Jan and I would giggle and roll our eyes and remind him, “Daddy, we’re the Garcias!”

“Yes,” he’d say, “but if they see the name Rockefeller on the list, they’ll know it’s somebody important.” And he had a very Rockefeller stride as he followed the hostess to our table: head up, shoulders back, friendly smile for everyone whether they smiled at him or not. I liked his Mr. Rockefeller persona. It didn’t even occur to me until I was an adult that this was his positive spin on the fact that seeing the name Garcia on the list might have prompted a different level of service.

Daddy was an avid videographer, who loved the newfangled cameras that were suddenly available to amateurs and everyday folks around 1980. He’d hoist the bulky unit onto a tripod, stick a VHS tape in it, and record every performance. He also learned to play the tambourine and Egyptian tabla (sometimes called a doumbek because of its hourglass shape), so he was part of the act as well. From my perspective, we were having a wonderful time together, but I know now that my father and mother had been cheating on each other for some time.

Dad went to Korea for a while, and when he came back, Mom had some serious questions about a woman with him in some of the photos he brought home. He was an unapologetic flirt, and it made me uncomfortable. I used to go with him to the local pawnshops and Radio Shack to check out the latest gadgets and geek out over the amazing advances being made in video cameras and recording equipment. I remember standing there while he chatted up some nice-looking lady. Sometimes those conversations went on longer than they needed to. I’d grab his wrist and pointedly say, “Daddy. C’mon. Mama’s waiting for us.”

At some point, she began seeing someone else, too. My parents’ relationship grew more and more strained, their bickering escalated to an uglier form of arguing and name-calling, and their marriage started to fall apart.

About that same time, a guy who was supposedly a family friend started hanging around our house, acting like the nicest guy in the world. My parents trusted him, but he violated their trust and mine. I was seven years old, so at first, I didn’t understand what was happening when he pulled me onto his lap. I didn’t know what he was doing or why he was doing it; I only knew it felt horrifying and bad. It made me sick inside, though I didn’t know how to explain it. I felt deep confusion. I tried to tell someone what had happened, but as is all too often the case, I didn’t have the vocabulary to call it what it was, and people didn’t want to believe it. I did everything I could to avoid him, but he found ways to corner me. Many times he suggested that I ride in his car to get something from his office.

“You should take Jan instead,” I always said, thinking that she was bigger than me, a big girl of eleven and a tough tomboy, so he wouldn’t be able to hurt her.

Years would go by before we could speak of it, but he did hurt her, too. When we were both in our twenties, sitting in my apartment in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, Jan finally confided in me that he had molested her. The grief and guilt I felt about that were quickly overtaken by a surge of raw rage on her behalf—and on behalf of seven-year-old me—realizing how this man had taken my power and made me feel shame for the first time. I decided to look him up and confront him. I rehearsed it in my head. Is this the man who violated a little seven-year-old girl? Whom I believed was a friend of the family? Whom my family trusted in their home? Who did things to a seven-year-old child that only adults do to each other? Are you that disgusting human being?

I dialed the phone, my ha

nds shaking, but before he could answer, I threw the phone down. The thought of hearing his voice nauseated me. All I could do then was pack these memories away in a dark corner of my mind, and I was okay with that for a long time. But one day, not long ago, while Gia was sleeping, it suddenly struck me how precious she is—so vulnerable, so innocent, so deserving of a safe, unruined childhood—and the thought of someone robbing her of her innocence and power and peace of mind triggered another unexpected surge of rage.

I sat down and Googled the man, thinking, I’ll sue him. I’ll post his name online and call him out for molesting my sister and me. Now I would be the one with the power and he’d be the one with the shame. I could get revenge. If I wanted to. But as I sat there with my hands on the keyboard, thinking about what that act of revenge would mean for me and Gia, how it would affect the quiet, joyful life I was making for her, the need for it faded. I believe in karma. God will take care of this guy when his time in this world is over, and he’s old now. His time is running out. Hopefully, his kids know what he is, but I know I’m not responsible for anything he did in his life—including what he did to my sister. The burden of thinking it was my fault is one more thing he had no right to inflict on me.

Seeing Gia now, I realize how very small and helpless Jan and I were amid the chaos of our parents’ failing marriage, even though we thought then that we were so tough. When Mama moved out of the house, leaving us with Dad, it was a relief in some ways. The man who’d molested Jan and me stopped coming around. The constant battles cooled to an uneasy truce, and even though she was living in her own apartment, Mama was in our kitchen waiting for Jan and me every morning when we got up, and she was there every evening to make supper and tuck us in for the night. I never felt abandoned by her—quite the opposite. She was on top of things, my most loyal ally, and still is today.

The Most Beautiful

The Most Beautiful